Settlers along the Wilderness Road: Part 2

Published 2:19 pm Tuesday, November 22, 2022

- Dr. Thomas Walker

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

JADON GIBSON

Contributing columnist

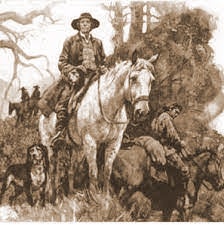

In the summer of 1773 Daniel Boone and captain William Russell led a party of seven families along Wilderness Road on their way to begin a new settlement in Kentucky.

Boone and his family and five others set out on September 25 with all of the belongings from their Yadkin River home in North Carolina. When they reached the area that is now Abingdon,Virginia, Daniel sent his 17 year-old son James, along with John and Richard Mendenhall northward to Captain Russell’s at Castle Woods to obtain flour and farming tools. Daniel and the rest continued along the wilderness trail through Big Moccasin Gap and across Walden’s Ridge before camping in Powell Valley. There they would rest until James and his party caught up with them.

Henry Russell, the 17-year-old son of Capt. Russell joined James’ party along with Isaac Crabtree and two slaves named Charles and Adam.

Capt. Russell had work to do before leaving and said that he and Capt. David Gass would catch up with them.

James Boone and his party set out on October 8 along the Fincastle trail and crossed the Clinch River at Hunter’s Ford, now Dungannon. They passed through Rye Cove and then followed the Wilderness Trail over Powell Mountain to the headwaters of Wallen’s Creek.

They began seeing signs that were probably made by his father’s group. He knew that they would meet up with them within a few miles but they decided to camp when darkness overtook them as they feared they may lose their way otherwise.

They tried to sleep after building a campfire and eating a scant meal but sleep was hard coming because of the howling of wolves. They felt the wolves were probably disturbed by the light of their fire.

“Oooooeeeeee, oooooeeeee,” Crabtree intoned sarcastically. “You boys might be mistaken for cowards. You’d better get used to it because in Kentucky even the buffaloes howl from the treetops.”

Late in the night the light of the fire dimmed and the howling of the wolves faded deeper into the woods. Soon it was dawn and a hush fell over the area except for the murmuring of Wallen’s Creek and the whisper of the wind in the trees.

Suddenly the quietness was pierced by the war whoops of a band of Indians as they rushed James’ party with raised knife blades and discharging guns.

Henry Russell fell with a shot through his hip and an Indian stabbed him several times. In an effort to protect himself Henry repeatedly grabbed the knife blade with his bare hand but after being wounded he was no match for the young warrior. He soon lay dead.

James Boone and the others were cruelly tortured before being murdered by the band of Cherokee and Shawnee who were supposedly under a truce. It was felt that the Indians may have been enraged by the plans of the party to settle on their hunting ground.

Isaac Crabtree hid in the woods and witnessed the attack.

A slave named Adam escaped with his life when he hid among a pile of driftwood. He later became lost in the forest for several days before finding his way back to Castlewood. Adam was freed from slavery by Madam Russell years later because of her sympathy for him.

The other slave (Charles) was taken prisoner and was forced to accompany the Indians. The Indians were aware of the value of slaves and often took them north to sell them. Charles was even less fortunate as two Indians had a continual squabble over who was entitled to the prisoner. The leader of the Indian party settled the quarrel by striking Charles with his tomahawk killing him.

Meanwhile Crabtree returned to Castlewood following the departure of the wild band of Indians since he did not know of Daniel Boone’s whereabouts.

Captains Russell and Gass came upon the horrid scene of the ambush the following day. They, along with the Boone party, had a simple ceremony and buried their dead.

Boone wanted to continue the journey into Kentucky following the Indian massacre of his son and others in 1773. He had sold his property on the Yadkin River in North Carolina and could not return. Capt. Russell persuaded him to abandon the exodus until the warlike behavior of the Indians abated.

Capt. John Stuart, the British Indian agent, urged the Cherokees to give up the murderers. One chief was executed and another fled. It was later learned that some of the attacking band were Shawnees.

Isaac Crabtree was the lone white survivor of the massacre. His life was filled with a continual rage against all Indians. He vowed to kill every Indian he encountered.

While attending a horse race in the Watauga settlement (now Elizabethton) he shot and killed Cherokee Billy, a friendly Indian who was a mere bystander watching the races. Two other Indians, one a squaw, were saved from Crabtree only with much difficulty.

Unfortunately, Cherokee Billy was kin to the influential Cherokee Chief Oconostota and, a renewed killing fervor was feared. Several settlers were able to avert a further bloodletting by expressing their disapproval of Crabtree’s conduct and by issuing a reward of 50 English pounds for his arrest. Gov. Dunsmore of Virginia pledged an additional reward of 100 pounds.

Several could have collected the reward but they knew individuals who had suffered from Indian attacks and refused to turn Crabtree in.

Editor’s note: Crabtree does more mischief and Boone treks into Kentucky in the next edition From the Mountains. Jadon Gibson is a freelance writer from Harrogate, Tn. His writings are both historic and nostalgic in nature. Thanks to Lincoln Memorial University, Alice Lloyd College and the Museum of Appalachia for their assistance.