Many towns have changed names over the years

Published 3:57 pm Wednesday, August 10, 2022

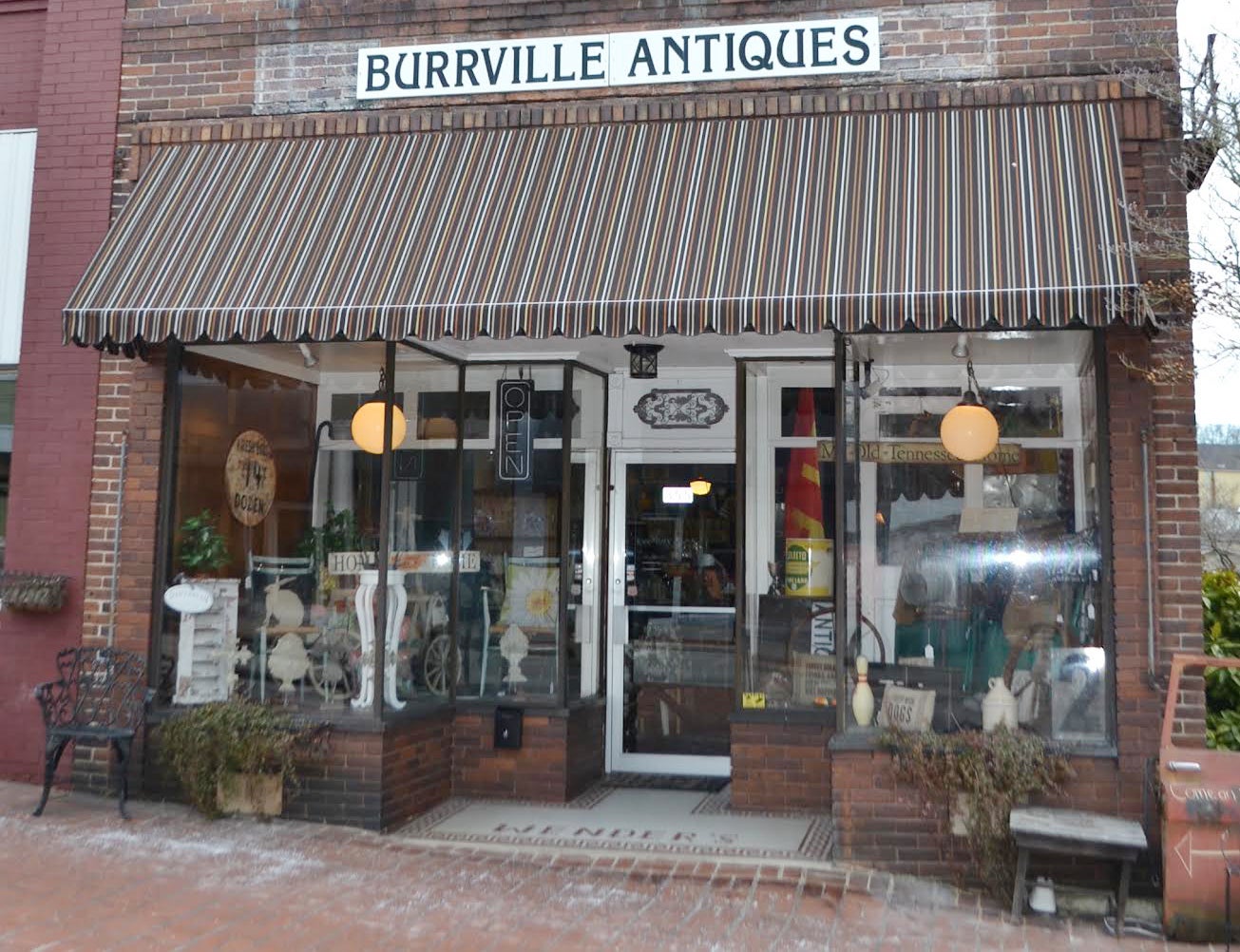

- The reason there’s a business in Clinton called Burrville Antiques is because the whole town once was called Burrville. Photo submitted

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

BILL CAREY

Contributing columnist

A few weeks ago, I wrote a column about how Benton County once changed the person that the county is named for without changing the name. This led a reader to ask me about how many towns in Tennessee have actually changed their names.

Quite a few, actually. In fact, here is only a partial list: The Anderson County seat used to be known as Burrville, but it changed its name to Clinton after Aaron Burr killed Alexander Hamilton. I supposed this makes Aaron Burr one of the early victims of “cancel culture.”

Gatlinburg was once known as White Oak Flats. In fact, there’s a cemetery in Gatlinburg called White Oak Flats Cemetery, just off the Parkway.

In its pre-incorporation days, Bluff City went by at least four different names: Choates Ford, Middletown, Union and Zollicoffer. (Zollicoffer was a Confederate general who was killed at the Battle of Mill Springs in Kentucky, after accidentally riding up to the wrong troops.)

Johnson City also went by at least four different names prior to its incorporation—Green Meadows, Blue Plum, Johnson’s Depot and Haynesville.

On my recent trip to the Rhea County seat of Dayton, I saw a display in the courthouse that explained that the town used to be known as Smith’s Crossroads.

Monterey was once known as Standing Stone because of a 12-foot-high monolith that existed in present-day Putnam County prior to the arrival of settlers. Unfortunately, most of it was destroyed by railroad builders.

In 1961, the Davidson County town of Dupontia (which had originally been named for the nearby DuPont plant) changed its name to Lakewood. Lakewood is now part of Metro Nashville.

The Monroe County seat of Madisonville was originally known as Tellico, or Tillico. I have run across this many times, since Tillico was a frequent stop on advertised stagecoach routes.

For a while, the West Tennessee town of Jackson was known as Alexandria. In fact, I have found ads for businesses that describe the community as Alexandria.

Prior to 1980, Farragut showed up on maps as Campbell’s Station.

Here are a few other names that I’ve either found or been told by readers over the years: Dover was called Monroe; Fairview was Jingo; Portland was Richland Station; Dickson was Smeedsville (with an “M”); Watertown was Three Forks; Alamo was Cageville; Savannah was Hardinsville; and there are many others.

So why have so many communities changed their names? According to Robert Brandt, author of Touring the Middle Tennessee Crossroads, a lot of them did because of confusion caused by other similarly named places. “For example,” he tells me, “there was already a Hillsboro, Tennessee, so the village in Williamson County changed its name to Leipers Fork. Crocker’s Crossroads sounded too much like Tucker’s Crossroads, so the locals picked the name Orlinda from a list the post office made available.”

However, over the years there have been several times where ambitious business leaders thought a name change would help the town. Here are a few examples:

Mossy Creek changed its name to Jefferson City in 1901. Newspaper articles about the name change indicate that officials from Carson-Newman College led the way in changing the name, because (apparently) they didn’t think people wanted to send their children to a college in Mossy Creek.

The Coffee County town of Manchester was known as Mitchellsville, but changed its name in an attempt to turn that community into Tennessee’s version of the industrial Manchester, England.

The Hancock County seat of Sneedville was originally known as Greasy Rock, which strikes me as a pretty cool title if the place had a microbrewery or rock festival. However, being known as the place where Native Americans used to cut up dead animals didn’t strike the residents of Hancock County as a good idea. So, in 1847, Greasy Rock became Sneedville.

Finally, in 1939, the Anderson County town of Coal Creek changed its name to Lake City. Its residents did this because coal mining had declined, Norris Dam was being built, and there was hope that a name change would bring tourists. Lake City never really took off, but hope springs eternal.

A few years ago, Lake City’s residents changed the name again, to Rocky Top, in hopes that the name change would result in the development there of a theme park. The state government changed all the signs along Interstate 75, but still no word about the theme park.

Bill Carey is the founder of Tennessee History for Kids, a non-profit organization that helps teachers cover social studies.